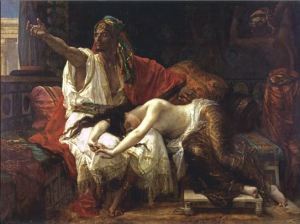

Genesis 37 is one of the most famous texts in the Hebrew Bible. In this narrative we read that Joseph—having been sold as a slave to the Egyptians due to jealousy by his brothers—is very beautiful. Beautiful enough that his master’s wife lusted after him and wanted to sate his lust. Repeatedly she commands, “Lie with me!” But he does not, until at last she forms a scheme to where she could isolate and rape Joseph: she waits until a time when there was no one in the house to bear witness or interfere with what would happen and again she commands him to lie with her. As has become famous in some circles, Joseph fled from her commands and advances, leaving his cloak in her hands. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned: Mrs. Potipher turns the blame on Joseph, convicts him of attempted rape, and Joseph is thrown in prison.

This text begs to be read alongside the text in our previous two posts. Consider the following:

In the only two occurrences of this term in the Hebrew Bible, Joseph and Tamar are described as wearing “multi-colored, long-sleeved coats” (“כְּתֹ֥נֶת פַּסִּֽים” Gen 37.3; 2 Sam 13.18).

Both Joseph and Tamar are first introduced in these specific narratives for their “beauty” (“יָפָ֖ה” Gen 39.6b; 2 Sam 13.1).

Both Joseph and Tamar are objects of fixation by their (attempted) rapists (Joseph has to “repeatedly refuse” “וַיְמָאֵ֓ן” Gen 39.8; Amnon was tormented for long enough to make himself ill, 2 Sam 13.2)

Both Joseph and Tamar are isolated in the house of their superior (Gen 39.11; 2 Sam 13.9).

Tamar reports the rape by “crying out” and Mrs. Potipher also makes a report by “crying out” (“וַתִּקְרָ֞א” Gen 39.14; “וְזָעָֽקָה\” 2 Sam 13.19).

Of course, there are two major points of contrast made by most exegetes of this passage. First, and most obvious, is that the innocent party in Genesis is a male, whereas the innocent party in Samuel is female. Second, Joseph is unfairly accused but punished, whereas Amnon is accused but not punished.

But before commenting on these conclusions, let us consider a few matters about slavery and rape in the ancient world.

It will surprise no one to hear that, within the broader context of the ancient world, slaves were property and not people. The penalties for murder, injury, theft, and rape were all severe in the ANE, these did not apply (or, at least, in the same way, consider Ur-Namma $8, which states that raping a virgin slave results in a 5 shekel fine payable to the owner, whereas raping a virgin freewoman was a death penalty in Ur-Namma $6; cf. Lipit Ishtar $d and $f for the varying penalties for striking a slave vs. a freewoman and causing her to abort her fetus).

|

| Demosthenes |

What might be more surprising, however, is that slaves present in the house or home were not just property, but sexual property. It was expected that slaves would be at the sexual beck and call of their masters, whether male or female. In fact, all of the laws dealing with slaves in the context of intimate relations are worried only about protecting the status of the master or mistress, rather than the slave. It is expected that the slaves will be raped, and thus most of the laws deal with the status of the children of these unions:

|

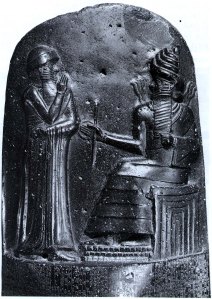

| The Stele of Hammurabi |

“If a man marries a free woman and the free woman gives a slave girl to her husband, and thus provides children, but then that man decides to married the slave woman, they will not permit him to marry her (Hammurapi $144).

“If a man marries a free woman and she does not provide him with children, and that man then decides to mate with a slave woman, that man may mate with the slave and bring her into his house as a concubine, but the concubine will not aspire to equal status with the free woman” (Hammurapi $145)

“If a palace slave boy or house slave boy mates with a woman of the upper-class and she conceives, the owner of the slaves will have no claims against the children” (Hammurapi $175)

This expectation is even more clearly indicated in the Greek and Roman descriptions of slaves.

We have mistresses for pleasure, slaves for daily service to our bodies, but wives for the procreation of legitimate children and to be faithful guardians of the household (Demosthenes, De Neaera,59.122).

You are her master, with full power over her, so she must do your will whether she likes it or not (Chariton, Chaereas and Callirhoe).

Unchastity is a crime in the freeborn, but a necessity for a slave (Seneca, Controversies 4, Praef. 10).

Now really, when your throat is parched with thirst, you don\’t require golden goblets, do you? When you\’re hungry, you don\’t turn your nose up at everything but peacock and turbot, do you? When you’re experiencing a hunger of a different kind and there is a slave girl or slave-boy ready at hand, whom you could use right away, you don’t require something better, do you? I certainly don\’t. I like sex that is easy and obtainable (Horace, Sat. 1.2.114–19).

Even the Roman moral giant—and slave himself—admits this will likely be the case.

In your intimate-life preserve purity, as far as you can, before marriage, and, if you indulge, take only those privileges which are lawful (i.e., with slaves), and make sure not to make yourself offensive or censorious to those who do indulge, and do not make frequent mention of the fact that you do not yourself indulge (Epictetus, Ench. 33.8).

The understanding that masters were likely, or even expected, to rape their slaves in the ancient world (because the slaves were not considered people at all) is recognized in the Hebrew Bible, as well, both in Law and in Narrative. We certainly see echoes of the situation discussed in Hammurabi $$144–45 in the discussion of Sarah and Hagar, or—although with less direct confrontation—the stories of Jacob, his wives, and their concubines. As we’ll talk about more in-depth in a future series of posts, there were two different sorts of slaves in the Old Testament with very different sorts of laws governing their use (debt slaves, which were Hebrews, and war slaves, which were foreigners). Foreign slaves were most commonly taken in war and were particularly subject to predation. It is for this reason that we read:

If after going to war . . . you see among the captives a beautiful woman, and you desire to take her to be your wife, and you bring her home to your house, you must first shave her head and pare her nails. She will take off the clothes in which she was captured and shall remain in your house and lament her father and her mother a full month. Only after that that you may go in to her as a man, and she must become your concubine. But if you no longer delight in her, you shall let her go where she wants; you may not sell nor may you treat her as a slave, since you have degraded her (Dtr 21.11–14).

As with the rape laws, this law has been appealed to frequently as an example of the horrible, immoral, patriarchy-driven, woman-hating nature of the Hebrew Bible. However—as with the rape laws—once we better understand the contextual framework for these laws, we find something quite the opposite. In the ancient world as we can see from some of the above laws (especially Hammurabi $175), and could see from many more, slaves were not only subject to the predation of their masters, but could—and would!—often be “loaned” to other guests for use as well. In fact, most brothels in the Roman world were filled with slaves. The Hebrew Bible does not deal with an ideal world, but the awful realities of the world. It does not forbid masters from taking their female captives as sexual partners (although, certainly, it could have); maybe because the authors knew this would never be followed. Instead, it attempted to channel the inclinations of the powerful to a lesser evil: masters could take their female (foreign) slaves as sexual partners, but not as slaves; they would become concubines (second-class wives) with the full rights thereof. They could not be given as sexual partners to anyone else; they were provided food, clothing, shelter, and legitimacy; their children would inherit as other children would; and if they were divorced—for any reason—they could not be reverted to slaves, but would instead be made free indeed.

|

| Narmer |

One more thing ought to be noted. In ancient Egypt, slaves were not only socially-inferior property, but were also considered genderless. In the relief depicting Narmer’s military victory, the Egyptians are careful to show the taking of war slaves which are portrayed as genderless (see the bottom of the left side), because they have been disgendered (and dismembered) upon captivity in both life and in death (see the right side). Even the captives’ clothing (which is always carefully portrayed in Egyptian reliefs and is a representation of identity) is carefully depicted to emphasize this emasculation process.

|

| Egyptian depiction of Foreigners; note the careful attention to detail |

With these things in mind, let’s look again at the case of Joseph and Mrs. Potipher.

As a foreign-born slave, Joseph was property and neither male nor female. He was at the service of his master and mistress, whether for managing the household or as a sex object. According to the laws and mores of the ANE and GR worlds, what Mrs. Potipher demands of Joseph is typical and lawful; it is Joseph’s refusal which would have been truly shocking and unruly (perhaps why she emphasizes the “laughing at us”?). Indeed, it appears as though Potipher himself must have insulated Joseph from punishment from Mrs. Potipher’s accusations of unlawfulness, and was only put in prison for the accusation of attempted rape of a free woman. More importantly, however, we understand that the balance of power is completely opposite of how we often view this situation. The stories of Amnon and Tamar and Joseph and Mrs. Potipher are not opposite texts about false witness, but are rather mirrored accounts of the powerful abusing their power to get away and trample on the truth of the powerless.

Let those with ears to hear, hear.

But something that we might not expect are the comments we read that this happened at a “moment in time” (4.5) and that, after, Satan retreats until “an opportune time” (4.13). This minor note invites us to read the passage a little differently than we probably are used to. It invites us to read this specific temptation in a broader sense, as representative of all of Jesus’ temptations and demands that we read Satan into all of Jesus\’ temptations throughout the Gospel. So, what I want to consider is how the three temptations of Christ in Luke 4 echo and are echoed in how Luke portrays temptation throughout, starting with the first. This is a sort of Midrashic Exegesis, a type of reading that was very popular in and around the first century and that considers individual stories as mere chapters in a broader, unified story (I’m planning on having a few posts on this phenomenon later, but for now you can just see it in action!). When we read stories this way, it can help highlight details and make connections that we might not otherwise make.

But something that we might not expect are the comments we read that this happened at a “moment in time” (4.5) and that, after, Satan retreats until “an opportune time” (4.13). This minor note invites us to read the passage a little differently than we probably are used to. It invites us to read this specific temptation in a broader sense, as representative of all of Jesus’ temptations and demands that we read Satan into all of Jesus\’ temptations throughout the Gospel. So, what I want to consider is how the three temptations of Christ in Luke 4 echo and are echoed in how Luke portrays temptation throughout, starting with the first. This is a sort of Midrashic Exegesis, a type of reading that was very popular in and around the first century and that considers individual stories as mere chapters in a broader, unified story (I’m planning on having a few posts on this phenomenon later, but for now you can just see it in action!). When we read stories this way, it can help highlight details and make connections that we might not otherwise make.