|

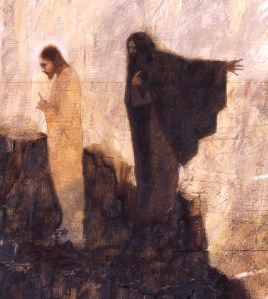

| Bottacelli’s Temptation of Christ |

One of the most famous stories in the Gospels is Satan’s testing of Christ in the wilderness:

Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from his baptism at the Jordan and was led by the Spirit through the wilderness for forty days, tempted all the while by the devil. He ate nothing during those days, so when they were ended, he was hungry. The devil said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become bread.” And Jesus answered him, “It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone.”

So the devil took him up and showed him all the kingdoms of the world in a moment of time, and said to him, “To you I will give all this authority and their glory, for it has been delivered to me, and I give it to whom I will. If you, then, will worship me, this will all be yours.” And Jesus answered him, “It is written, You shall worship the Lord your God, and him alone shall you serve.”

So the devil took him to Jerusalem and set him on the winged-pinnacle of the temple and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for it is written, He will command his angels concerning you, to guard you, and On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone.” And Jesus answered him, “It is said, You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.” And when the devil had ended every temptation, he departed from him until an opportune time (Luke 4.1–13).

This temptation is symbolic of

all temptations because all temptations come from Satan. But Satan had failed twice already. First (as we discussed

earlier), for Jesus take advantage of his status as the Son of God and remove temptation by breaking bread from stone, which would keep Jesus from becoming bread broken in our place. Second (which we also

surveyed), he had failed to force Jesus to receive his power and authority from that old serpent, Satan, thus rendering him unable to crush the serpent’s head and allow his disciples to tread upon serpents as well. But there was one last great temptation with which Satan could tempt Jesus, the Son of God.

But what is the temptation? We know Satan takes Jesus to the winged-pinnacle of the temple and tells him to jump, but we don’t know much of anything else. Is the temptation for Jesus to perform a miracle in the eyes of the Jerusalemites, thus saving himself from death? Jesus performed many miracles, even in Jerusalem; none stopped the crowds from hating him or killing him once they understood what he was actually saying. Instead, I think it is better to understand that Satan was tempting Jesus with

proof: proof that God would indeed save him, proof that God would save and protect him from death

now, rather than hoping that God would save him at the end. He would force God’s hand, put him to the test, like the Israelites who—at Massah and Meribah—put God to the test when they were thirsty by asking “Is the LORD among us or not?” (

Exd 17.7). “We are his children! We are thirsty! Prove, God, that you love us and will protect us! Give us water

now.” Jesus here is tempted to walk by sight and not by faith (

2 Cor 5.7). Satan asks, “Will God save you, or not?”

|

| Chagall’s Moses and the Rock |

Satan

took him to Jerusalem because Jerusalem is and has always been the goal. At the transfiguration, Elijah and Moses appear in glory and spoke about his departure, which he was to accomplish at Jerusalem (

9.31). A bit later, we see that Jesus embraces his death and begins to speak more clearly about the kingdom because it was time for him to turn his face to Jerusalem (

9.51). Jesus says that he must go on his way because it cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem, that city that kills the prophets and stones them who are sent to her (

13.33–34). When they are near, he takes the twelve aside and said “See, we are going to Jerusalem where everything that is written about the Son of Man by the prophets will be accomplished” (

18.31). If Jesus had leapt from the winged-pinnacle (

πτερύγιον, which comes from πτέρυξ) of the temple in Jerusalem (

Luke 4.9), he would no longer be the Jesus who longed to gather Jerusalem under his wings (

πτέρυξ), like a hen gathers her chicks (

13.33–34). If Jesus had not trusted in God, walking by faith to Jerusalem to die, no longer would repentance for the forgiveness of sins be proclaimed to all nations, beginning with Jerusalem (

24.47) because the winged-veil (

καταπέτασμα) of the temple would not have been torn in two (

23.45).

Satan tempts him not just with sight, but with Scripture. Quoting from Psalm 91, he tells Jesus that he should tell God to prove that he will do what he is promised, that he will command his angels to guard you in their hands lest you strike against stone (

91.11–12). But if he had put God to the test, he would not—as the next verse of the Psalm says—have been able to tread upon the lion and the adder, the young lion and the

serpent (

91.12). Because rather than sheltering under the shadow of his wings (

91.4), he would have leaped from them (

Luke 4.9). Had Satan succeeded in getting Jesus to have angels rescue him now, he would have had the angel rescue—rather than strengthen—him in the Garden (

22.43). Should Jesus force God to protect him in the hands of angels now, he would never have the faith to be delivered into the hands of sinful men, be crucified, and only after—on the third day—rise (

24.7).

As shocking as it may seem, this temptation to walk by sight and not by faith is something that Jesus struggled with throughout his time on earth. He was identified with our condition in the flesh; he too was plagued by these difficulties. He is tempted in every way as we were and here—when tempted—he does not appeal to his status, which Satan is so kind to remind him of, as Son of God, but instead acts as the Son of Man: he prays, he considers Scripture, he considers God. Jesus went to the Cross based on faith, not on sight.

Jesus had faith and obedience in the Wilderness where no one else obeyed and so he had faith and obedience in the Garden where no one else obeyed. Luke does not mention Adam in this narrative, but he clearly has him in mind. Luke has moved Christ’s genealogy from the beginning of the story (as it is in Matthew), to just before the temptation. And rather than beginning with Abraham and moving forward to Jesus, he begins with Jesus and moves back to

Adam. The last verse of chapter three, immediately before the temptation begins, reads “Adam, the son of God” (

Luke 3.38). Through the first Son of God, sin entered the world. But through the Better Son of God, might Better Life (

1 Cor 15.22;

15.45;

Rom 5.18–19) in the Better Garden (

Rev 22.1–2).

All of this is possible only because Jesus refused to force God to keep his foot from striking against stone, so that he could become the stone that the builders rejected, the chief cornerstone (

Luke 24.17) who—after death and resurrection—would roll away the stone of the tomb, of sin, and of death (

24.2).

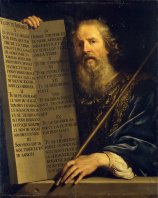

The Transfiguration displays the glory of the son, he is not one of three great men, but the Son of Man. Thus, the gospels informs us, the apostles need not build three tabernacles, nor even one, because Jesus came and tabernacled among us. Jesus is the better Elijah, who did not require a sign of God’s protection prior to doing his will at the end of 40 days in the wilderness (

1 Kgs 19). Jesus is the better Moses, who after 40 years in the wilderness neither struck the stone nor demanded that God keep his foot from striking the stone (

Luke 4.11).

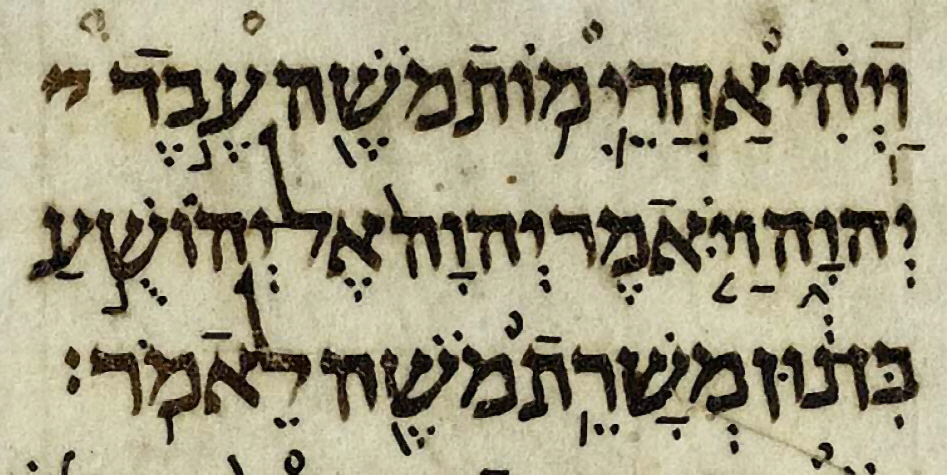

At first, these passages seem incredibly similar! There are only two changes which seem pretty slight: the Greek passage includes that Moses went into the mountain and removes that God called to Moses. But what changes is that Moses no longer has unmediated access to God in GrEx like he does in the MT! Taken alone, this wouldn’t be a big deal: maybe the scribe(s) just made a mistake; maybe it’s just a quirk of translation; but it isn’t. These sorts of changes accumulate into a consistent theologically-driven decision.

At first, these passages seem incredibly similar! There are only two changes which seem pretty slight: the Greek passage includes that Moses went into the mountain and removes that God called to Moses. But what changes is that Moses no longer has unmediated access to God in GrEx like he does in the MT! Taken alone, this wouldn’t be a big deal: maybe the scribe(s) just made a mistake; maybe it’s just a quirk of translation; but it isn’t. These sorts of changes accumulate into a consistent theologically-driven decision.