I lift my eyes toward the mountains

From where will my help come?

My help comes from the LORD,

the Maker of heaven and earth.

He will not allow your foot to slip;

your Protector will not slumber.

Indeed, the Protector of Israel

does not slumber or sleep.

The LORD protects you;

the LORD is a shelter right by your side.

The sun will not strike you by day

or the moon by night.

The LORD will protect you from all harm;

he will protect your life.

The LORD will protect your coming and going

both now and forever (Psa 121).

“He will not allow your foot to slip; your Protector will not slumber. Indeed, the Protector of Israel does not sleep or slumber.” Psalm 121 comforts us because our God on whom we rely does not sleep even though we must. Indeed, this is the very point that Elijah the Prophet makes when he is insulting Baal and his prophets on top of Mt. Carmel—“Cry louder, isn’t he a god? Is he still thinking it over? Is he stuck in the bathroom? Is he on a journey? Maybe he’s asleep and must be awakened!” (1 Kgs 18.27). Baal may sleep and thus be unable to hear or answer the call of his worshippers, but the Protector of Israel does not sleep or slumber.

The priests of Baal thrash and flail,

A Reflection on 1 kgs 18

Shedding blood and weeping,

Whatever they try, they cannot prevail

Because their god is sleeping.

Elijah, on the other hand, knows that the LORD does not sleep nor slumber. So, while the prophets of Baal wear themselves out, he rests until his time comes to serve. Elijah knows this. But it’s easy to remember when things go well; it’s harder to remember when things go poorly. This is true for us just as it was for Elijah, for when things do not turn out as they should, Elijah forgets: after Elijah defeats these prophets, he and Ahab deliver the message of God’s victory to the Baal-worshipping Jezebel. Jezebel, far from being impressed at the LORD’s greatness and power, promises to kill Elijah; and Ahab, far from remaining faithful to the LORD whose power he has just witness, allows this edict to stand. There is no revival; there is no purge of Baalism; there is no victory.

Elijah, depressed and deflated, tired and worn—having spent years alone or in exile, and now thinking that this was all for nothing—forgets what he knows: that the God of Israel neither sleeps nor slumbers; he thinks that he must save his own life. He runs as far away from this threat as he can, first as far south as Beer-sheba, and then even further south into the Wilderness where his ancestors died for their lack of faith—he sits under a broom tree and prays to the LORD:

“I have had enough! LORD, take my life, for I’m no better than my ancestors!

1 Kings 19.4

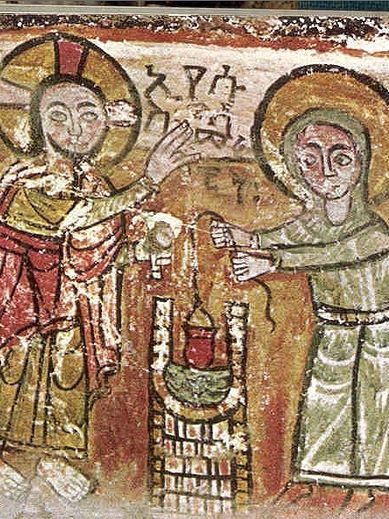

And, there, exhausted and worn, having run as far as he can, having prayed to die, he lays down and goes to sleep after praying he would not wake. The image that we have is that he—like the priests of Baal on Mt. Carmel before him—has exhausted himself trying to make something happen because he thinks his God is asleep and cannot hear his cry or will not save him. But this sleep does not provide him hope; it does not provide him comfort; it does not provide him rest.

You see, it’s hard to remember that our God neither sleeps nor slumbers, that—as David says as he too flees south from his enemies—we can lie down and sleep, waking safely because the LORD sustains us (Psa 3.5), because he is a shield about us, our glory, and the lifter of our head (Psa 3.3). It’s hard to remember this and to have faith when we are held by fear, terror, and sleeplessness. When you are terrified, it is impossible to go to sleep! Sometimes when you’re overwhelmed, you’re too tired to even sleep. When you don’t feel safe, don’t feel loved, don’t feel protected… That’s why—as we talked about last time—so often we turn to worldly things to gain sleep, because we must drown out these fears and these regrets first.

This is how Elijah feels. But when God comes to this exhausted Elijah under a broom tree, he sends his angel to feed him and tell him to sleep (1 Kgs 19.6–7). But when Elijah awakes this time, having been sustained by the LORD so that the journey God has planned is no longer “too much for you,” something has begun to change. Elijah goes to the Mountain of God, where God speaks to Elijah in wind and earthquake and fire and whisper. And that change has continued to grow. Having been—like Israel before him—sustained by God’s bread in the Wilderness, and (like Moses) spending time on Sinai with God and (like David before him) provided rest and reassurance by God, Elijah once again takes hold of faith. Elijah is about to do this not just because of knowledge that 7,000 knees haven’t kissed the Baals; and not just for having seen God’s miraculous abilities. It’s because, after being fed in the wilderness, and seeing God, and being provided sleep and rest, he has learned something about God in a way he had not known before.

Elijah learned on that Mountain what we all have to learn. We’re all weak. We all need sleep. We all may—like my children still do—pretend we’re not tired; that we don’t need a nap or quiet time or whatever (the Venn diagram of times where my children will making a big deal out of everything, where everything either makes them rage (Hadassah) or wail (Abigail), and when they need sleep is very nearly a perfect circle…). Still, each time they insist “I’m not tired!” And I respond, “Honey, if you weren’t tired, you wouldn’t be acting this way.” But here’s the thing, even as we grow out of childhood and into adulthood… we don’t change that much. Why do we have to go to bed? We have things to do! Things we want to do; things we need to do; things that we…

Why do we sleep? Have you ever wondered that (and have talked about it before)? I don’t of course pretend know any of the psychological or neurological reasons behind it—but I think about it from a biblical perspective a lot. Because, as some of y’all know…. I don’t sleep a lot. Back when I was a professor there was always more things to do—emails to answer; course content to upload; make-up assignments to grade; student questions to answer; hospital visits to make; classes to build; lectures to write… And even now that I’m not, and I’m “just a preacher,” there’s still the same sorts of lists: classes to prep, social media posts to make, sermons to plan, visitors to follow up with, folks to pray for, personal study to pursue, emails and texts to answer, folks to check up on…. I sometimes wish I didn’t have to sleep. Sometimes, I pretend I don’t need to sleep. You realize we spend about a third of our lives asleep? Why? Why does God make us sleep? What is it’s purpose?

I think the answer is in what we have seen. It’s because we’re not God and we need to recognize that. God doesn’t sleep or slumber, but we must. And the longer we try and grasp that forbidden fruit—plying ourselves with coffee and tea, Monsters and Nitrosurge—the more our ability to function degrades. We are forced to realize what the Psalmist has already told us:

Unless the LORD builds a house,

its builders labor over it in vain;

unless the LORD watches over a city,

the watchman stays alert in vain.

In vain you get up early and stay up late;

working hard to have enough food—

yes, he gives sleep to the one he loves (Psa 127.1–2)

Sleep then, especially when life is toiling around us and life is calling out to us to serve ourselves and protect ourselves and do more for ourselves, demonstrates dependence on, surrender and submission to God. Because when we sleep we are utterly and entirely helpless. We cannot write papers while we sleep; we cannot worry while we sleep; we cannot work while we sleep; we cannot watch out for ourselves or protect ourselves or trust in ourselves while we sleep. Instead, it forces us to entrust ourselves completely to the care of the LORD, losing control of everything.

Why do we sleep? Because one day, we will die. One day we will all sleep. So if we will trust in God to wake us, we must trust in him to sleep.

Fred Sanders says it this way, “Sleep is good practice for death. It’s good preparation for life with that same God who you’re going to have to trust eventually. And it’s worth asking for sweet dreams, because he gives sleep to his beloved, and he gives to his beloved in their sleep.”

And, as St. Paul might add, for those of us who do entrust ourselves to Christ, then death becomes just like sleep, from which we will all awake. God creates Eden after banishing the darkness and creating light but that night grew long as the curse took hold. But when this world is over and God creates the New Heavens and the New Earth, he will not just banish the darkness during the day, but forever. As Revelation says,

There will no longer be any curse. The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will worship him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. Night will be no more; people will not need the light of a lamp or the light of the sun, because the Lord God will give them light, and they will reign forever and ever (Rev 21.3–5)

When I lay me down to sleep

I pray the Lord my soul to keep

If I should die before I wake

I pray the Lord my soul to take.When I lay me down to sleep

A Prayer

I pray the Lord my soul to keep,

Watch and guard me through long night

and wake me with eternal light.