One of the type scenes (or tropes, like the Woman at the Well) folks run into in the Bible is also one of its most prevalent metanarratives: “Cities are bad.” You look at Babel, Sodom and Gomorrah, or Gibeah and quickly realize “No, cities are really bad.”1 But sometimes we don’t think further about why the Bible’s authors tend to portray them that way. To figure out way, we need to begin at the beginning. To figure out all of it, we’ll have to work to the end.

God planted humanity in a Garden. In that Garden, they were given commands to be fruitful and multiply (Gen 1.22, 28) and to tend the Garden (Gen 2.15). They implication of this narrative (and, in many ways, one of the Metanarratives of the Bible as a whole!) is thus “grow the Garden until it fills the earth.” A divine mandate poured into a coffee cup that reads “grow where you’re planted.” We know, of course, how this went: exiled from the Garden because of their sins, forced to wander, longing for home, they settle and Adam continues to bring offerings to the East of Eden.

But even when we cannot have the home in the Garden, we still long for a home. The sins of the father pass on to the son–and in the wake of his own failure at the agricultural mandate and his own subsequent exile–Cain seeks to make a home for himself so he’d feel less like an exile.2

When Cain was intimate with his wife so that she conceived and then gave birth to Enoch, Cain built a city and he named the city ‘Enoch’ after his son (Genesis 4.17).

Cain built a city because the land wouldn’t support him at all (Gen 4.11–12). After all, he was exiled not only from his family and from his home, but from his profession as farmer. When Cain set aside mud for mortar, he becomes the first person to build a city in the Bible–but far from the last. But he begins something that we’ll see carry on through the Spiritual Geography of the Bible–those who build cities aren’t doing the right thing; it’s most often an act of prideful rebellion as an attempt to end God’s exile without fixing the problem that led to it. “We’ll make a place for ourselves where we’ll belong and we don’t need your Garden or you.” The most famous example, of course, is found just a few chapters later in Genesis:

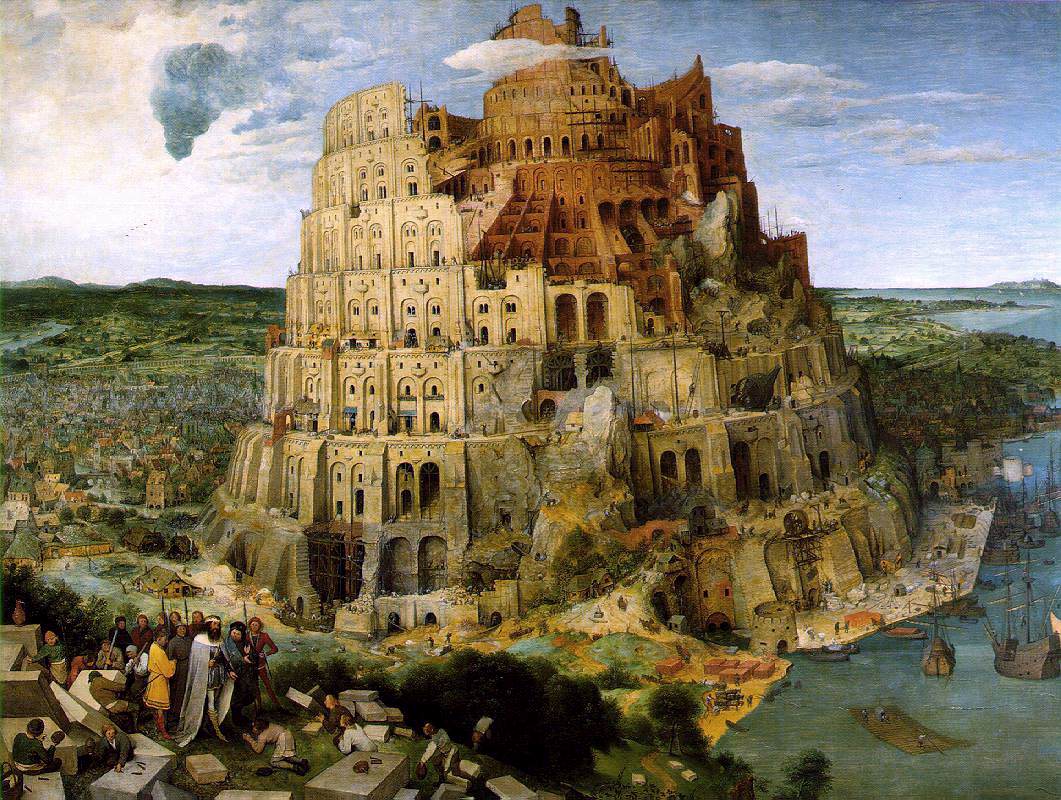

The whole earth had the same language and vocabulary. As people migrated from the east, they found a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there. They said to each other, “Come, let’s make oven-fired bricks.” (They used brick for stone and asphalt for mortar.) And they said, “Come, let’s build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the sky. Let’s make a name for ourselves; otherwise, we will be scattered throughout the earth” (Genesis 11.4)

Here, it’s clear: They’re trying to reverse God’s scattering which would lead them to fill the earth; they’re avoiding being wanderers; they’re far from the Garden; they want a tower with its top to heaven so that they might have a home for themselves (or perhaps even take over God’s home?). But God is not mocked and just as he does not dwell in structures made by human hands, nor can structures built by our own hands ever truly provide a home. This story ends much as the first search for a city began: with exile, being scattered, and displaced across the earth (Gen 11.5–9).

But this isn’t the only example of a city! Cities throughout the rest of the Bible that are working on this same narrative end the same way: rebellion, wickedness, and questions of exile vs. home pervade these city narratives! Just consider the following briefly.

- Sodom and Gomorrah are cities who treat those who are wanderers or exiles horrifically, are dens of wickedness, and are ultimately destroyed by God even though Lot longs to have his home there (Gen 19).

- Gibeah in many ways retells the story of Sodom, but this time it’s an Israelite who thinks he’s found a home and safety in an Israelite city, but is still seen as a wandering exile upon whom to prey but it too is destroyed by God (Jgs 19).

- Gezer is a city that Solomon builds to provide a “home” to his Egyptian bride, even as he becomes more and more like Pharoah himself, with his own “home” destined to be destroyed (1 Kgs 9).

Cities we build for ourselves are bad and bad things happen in them and to them! It really couldn’t be clearer. But those aren’t the only types of cities in the Bible, and the Bible’s treatment of cities is more complex than simple anti-urbanism. But for the positive reading of cities, we’ll have to wait for next time.

Footnotes (since WordPress doesn’t actually support this, right now…

1) Lots of folks have talked about these connections! The Bible Project has a new video on cities, as well as a longer discussion on their podcasts. There are numerous articles and even entire books dedicated to these ideas. Everyone’s take aways are slightly different (I once got into a bit of a tizzy with JMH at a conference over this!), but they’re all worth your time.

2) The issues with Cain and Abel are complex. But there’s a lot of folks–from antiquity until today–that don’t just see this as a confict between brothers, but also between urbanization and rural living, between farmers and pastoralists, etc. Lots has been written on this as well! I’d definitely recommend this if you’re interested in how other such stories play out in the ancient world. If you’re just interested in the question of the sacrifice, check out Wayne’s post.

2 thoughts on “Living as Exiles: Cities and Sin”