A few posts ago, I talked about how intertextuality—the practice of lining up two or more texts that are close enough to compare in order to emphasize differences or help aid in interpretation—can help us better understand the Bible. Both of these posts used Genesis 19 to show how this text can help us better understand other texts which align in similar ways (like comparing Lot and his Daughters to Noah and Ham, or Sodom and Gomorrah to Gibeah).

Let’s look at another, more disputed text. I’m going to explain a story to you (without names!) and you tell me if you can figure it out.

There’s a family living in Israel and this family has a long and unfortunate history of family strife; lying, cheating, and stealing are depressingly common. The Patriarch of the family has grown old and infirm, and greatly favors his oldest son, even though it seems God has favored the younger son. But the mother favors the younger son and wants him to run the family and inherit his father’s position and promise. So, the mother cooks up a plan to deceive her husband steal control of the family for her son from the favored older son. God’s plan, of course, come to pass, but not the way it was supposed to happen. Instead, we see a family rife with deceit and machinations that causes still further problems in the life of the son who himself inherits.

|

| I love how Rebekah is always RIGHT THERE. |

“Ah! I know that story!” you might say. “It’s Genesis 27!” And you’d be right! You remember the basics: God told Rebekah that the younger would rule over the elder, but Isaac favored Esau, the older son instead of Jacob, the younger. So, while Isaac planned on giving Esau his blessing, but—while Esau is in the process of procuring the means to gain the blessing—Rebekah connives to get Jacob the blessing first. God’s will is done, but not according God’s will. Deceit, deception, and outright lies “win” the day. But only for a day, because these practices and decisions continue to cause problems for Jacob and the rest of his family throughout his story.

But you’d also be wrong. Because there’s another episode with different characters in a different setting that nevertheless fits this same telling of events.

|

| “Mom, seriously, be quiet or he’ll totes hear you!” |

It’s 1 Kings 1. You probably remember the basics: David is old and infirm—like Isaac, confined to his bed (1 Kgs 1.1–4)—and he has continually favored his eldest son: first Amnon (make sure you check the DSS and the LXX version of this verse!), then Absalom, and now Adonijah. There is every indication that David intends to give his blessing and his throne. But Bathsheba, Solomon’s mother, wants Solomon to be king after David’s death. And so, while Adonijah is in the process of raising support for his own coronation, Bathsheba devises a plot to gain David’s blessing first. God’s will is done, but not according to God’s will. Deceit, deception, and outright lies “win” the day. But only for a day, because these practices and decisions continue to cause problems for Solomon and the rest of his family throughout the story.

|

| Why is Rebekah ALWAYS THERE |

“But wait!” you might object, “There wasn’t any lying or deceit going on in 1 Kings 1! Bathsheba said that David had promised her that Solomon would inherit the throne and Nathan the Prophet is involved. No way was she lying.” Those are important points and this reading certainly matches the way we tend to think through this text. But we need to be careful not to read teleologically (reading the story as if it always had to play out that way just because it happened to play out that way).

Consider, two quick counter points.

Bathsheba does indeed tell David that he had promised her that Solomon would inherit the throne. But if he did, it’s nowhere else recorded (not even in 2 Sam 12, where we would expect it!), and God’s promise to David is notably vague about any particular son inheriting his throne (2 Sam 7). Equally problematic is that, if David told Bathsheba that her son would inherit the throne, he certainly hasn’t acted like that. He treated Amnon as the heir apparent, then Absalom the same, and is fully aware of what Adonijah is doing and how he has been acting as the crown prince and has said nothing to him about it! Adonijah has cause to lie, but seems to think that Bathsheba might believe that “All Israel fully expected” him to take the throne after David (1 Kgs 2.15). If anything can be discerned from the story, it’s that David favored Adonijah. Lastly, we should at least consider the possibility that even if David had told Bathsheba that her son would inherit the throne, that doesn’t mean he was telling the truth. David just might have lied a time or two in his life.

|

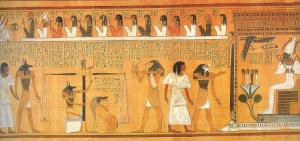

| It’s even drawn similarly! |

The second, more substantive, question involves Nathan’s involvement. Nathan is a Prophet and has been nothing but faithful from what we’ve seen in the story so far! Surely, a prophet wouldn’t lie or be mistaken? After all, Nathan himself was the one who delivered the message of David’s adultery with Bathsheba, the death of his firstborn, and the promise of Solomon’s birth (and naming)! Perhaps Nathan had some special revelation about Solomon inheriting the throne? All of that is either true or possibly true, but—if the implications are true—they arise from Nathan’s character and not from the text. In the text itself, things are a little different. Nathan is worried about Bathsheba’s and Solomon’s lives, not primarily about him gaining the throne (1 Kgs 1.12). Nowhere does he mention a promise that God made to him, or David to Bathsheba. Indeed, the plan he puts together is crafted as subterfuge! “First you go in…” then, “I’ll come in as if by chance, after…” to “confirm what you say” since it would require at least two witnesses! We might also want to remember that–in the book of Kings–prophets (even good ones!) are often less than dependable in their grasp of what God wants them to do. Furthermore, if Nathan is on the side of Solomon as a faithful servant of David and God, then Abiathar the Prophet is on the other, a faithful servant of David and God as well, and for even longer.

What emerges isn’t entirely clear. Are Bathsheba and Nathan lying, or telling the truth? Did David mean Solomon to have the throne originally, or not? There are good arguments either way and scholars have long debated this issue.

But one thing is certain, without making the connection between 1 Kings and Genesis, between Isaac, Esau, Rebekah, and Jacob and David, Adonijah, Bathsheba, and Solomon, we probably wouldn’t even be asking these questions. And, as we’ll talk about next time, opening our eyes to this possibility raises our awareness to other elements present in the Solomon narratives in 1 Kings.